The New York Times: Time of Women

11- 26.11.2015, 15:12

- 21,997

A new play, based on the harrowing experience of jailed writer Irina Khalip, highlights the dangers that women fighting for democracy face in Belarus.

Irina Khalip, a Belarusian journalist, editor, and activist, won’t let her country, commonly referred to as ‘the last dictatorship in Europe,’ make the same mistake twice. “The problem is that people in my country didn’t fight for freedom” after the Soviet Union dissolved, she told a packed house at London’s Young Vic theater on Tuesday evening. “You know, we [thought] freedom fell from the tree, like ripe fruit. We didn’t know it was a value you should fight for, we took it for granted, and that was a mistake.”

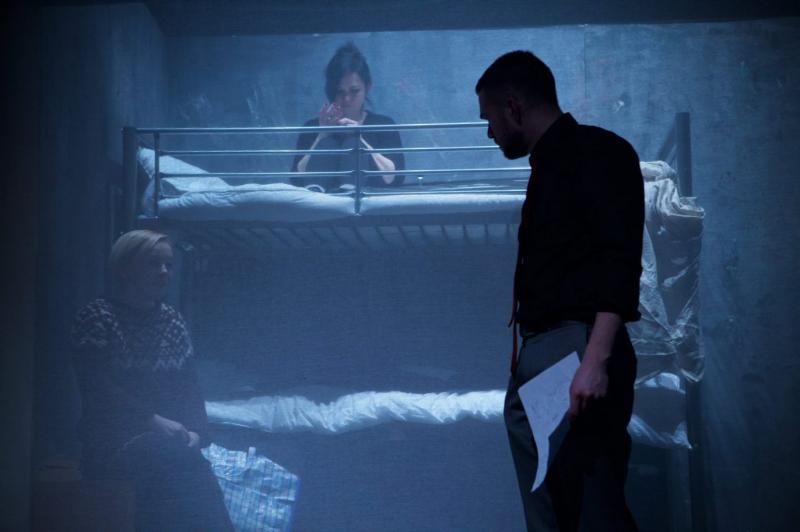

Khalip graced the stage following the U.K. premiere of the Belarus Free Theater’s Time of Women, a new play that depicts her imprisonment by the Belarusian K.G.B. due to her role in peaceful protests against the country’s unfair presidential elections in December 2010.The performance is part of a 12-day festival in London called “Staging a Revolution,” running from November 2 to November 14, The New York Times reports.

Khalip’s husband, Andrei Sannikov, was the leading opposition candidate against Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenka, who claimed to have won with 80 percent of the vote. (Lukashenko won a fifth term in office with a reported 83.5 percent of the vote in elections this October.) Sannikov was subsequently beaten and both he and Khalip were arrested after taking to the streets to protest the results, as were 600 people who joined their cause. Time of Women begins with a recording of the violent moment of their detention.

Directed by Nicolai Khalezin and Natalia Kaliada, a Belarusian husband-and-wife duo, the performance deliberately highlights the particular dangers that women fighting for democracy face in Belarus. “After the elections in 2010, all the men were arrested,” said Kaliada, who fled her home country in 2012 and now lives in London. “Those who were left outside, they were mothers, sisters, friends…They started to run all the campaigns, to put pressure on politicians…it was just the clear thing to do – women stood up for their loved ones.”

Khalip was imprisoned along with fellow journalists Natalya Radina and Nasta Palazhanka, who also protested the election, and the three of them spent Christmas 2010 in a dark, cold cell together. Time of Women tells the story of how they were abused and manipulated by their handlers, who tried to get them to turn against one another and threatened them with hard labor, malnourishment, and losing custody of their children. “By the time you get to the [penal] colony, you’ll have aged 10 to 15 years,” Colonel Orlov, the prison K.G.B. officer (played by Kiryl Kanstantsinau), warns, reminding them that all the hardship might make them infertile. In the face of those dangers, the play shows how the women keep each other sane and strong, reading Joseph Brodsky poems, romance novels (the only literature allowed inside the prison), and singing patriotic songs.

“All the words in the play were really spoken in the K.G.B. prison,” Khalip told the audience after the performance. Directors Khalezin and Kaliada are close friends of her family, and made sure to record their testimony after their release. The directors also sent the play’s cast, the Belarus Free Theater’s Maryia Sazonava, Yana Rusakevich, and Maryna Yurevich, to spend time with their real-life counterparts.

Khalip was transferred to house arrest after being imprisoned for nearly two months, and relayed her experiences to Kaliada via Skype. House arrest “was even more terrible than prison, because in prison you know exactly – you’re here, your enemies are there, behind the iron door,” Khalip said. “When you are under house arrest in Belarus you have two K.G.B. officers in your flat. They live with you, they look after you 24 hours [a day]. They can, for example, come into your bedroom in the middle of the night, just to check. They can stand behind their bathroom door and listen, and ask, ‘How are you? Everything ok?’ This is real torture … My three-year-old son was with me under house arrest, he also couldn’t go out from the flat. So I was not released, I was just moved from one prison to another.”

In May 2011, Khalip was given a suspended sentence of two years in prison. “For two years, all these people, police, K.G.B. officers, will come to your flat every evening after 10 p.m. because you’re not allowed to go out in the evening. You have to go to the police station every week…I was released in reality, in fact, only in 2013, after three years of these tortures.”

Her husband, Andrei Sannikov, was sentenced to five years in prison, but was pardoned by President Lukashenko in April 2012. While many of their friends have fled the country, Khalip still lives in Minsk, where she continues to work as an “absolutely illegal” journalist, as she put it. “I work like a partisan. But there was a very strong partisan movement in Belarus during the second World War, so for us in Belarus partisan work is normal.”

The outlook for women’s rights in Belarus remains less than promising. After the December 2010 protests, one of the few women in Belarusian politics, Central Election Commission head Lydia Yermoshina, addressed her countrywomen in a speech with the following advice: “You had better sit at home and cook borscht instead of going out to the streets.”

“It’s a very Soviet attitude towards women,” said Kaliada. “There is a very new generation of women who are educated and very sophisticated… they’ve become real fighters, they’re a driving force behind a lot initiatives for democratic changes. It’s divided. The people who stay in power, they insist there is no role for women in society.”

But if there is hope for change, it rests in large part with Khalip, Sannikov, and their friends. “Now we know freedom is a real value – we know its smell, we know its taste,” Khalip said.

“These are the people who you really want to lead the country when it’s a democracy,” said Kaliada. “These are absolutely amazing and empowering women.”

The Staging a Revolution festival continues until November 14, at the Young Vic Theater, London.