The Women of Charter

9- 9.01.2017, 13:00

- 19,143

Czechoslovakian movement Charter 77 was created 40 years ago but even today its ideas still inspire freedom fighters around the world including Belarus.

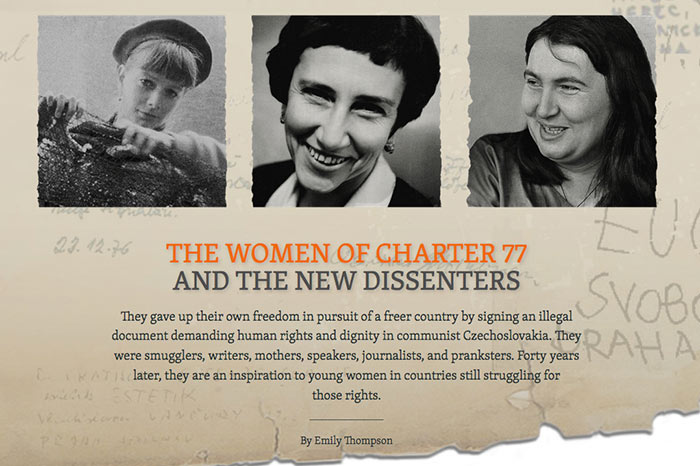

They gave up their own freedom in pursuit of a freer country by signing an illegal document demanding human rights and dignity in communist Czechoslovakia. They were smugglers, writers, mothers, speakers, journalists, and pranksters. Forty years later, they are an inspiration to young women in countries still struggling for those rights.

On January 7, 1977, a short and humble text appeared in the pages of some of the largest Western newspapers, including The New York Times and Le Monde. Written in Prague, Czechoslovakia a few days earlier, it was read out and discussed in the original Czech that day on the airwaves of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Voice of America. Both broadcasters were officially banned in communist Czechoslovakia at the time — as was the text itself, which circulated in “samizdat” or self-published form only. The authors and the 242 original signatories called the text “Charter 77,” and their demands were modest: that the government respect human rights as stipulated in the country’s own constitution and in international agreements like the 1975 Helsinki Accords, and that citizens be free from persecution and fear of persecution for expressing their opinions.

The government’s response was swift and brutal. Those associated with the charter were called traitors and imperial agents; many of them were imprisoned, dismissed from their jobs or university studies, spied on, and threatened. Over the next 12 years, the Charter 77 dissidents wrote thousands more pages describing the kind of society they wanted to live in, and they gathered more signatures, all at great personal cost.

Finally, in 1989, the Velvet Revolution brought a peaceful end to the communist regime in Czechoslovakia. One of the brightest luminaries of the Charter 77 movement, playwright Vaclav Havel, served as the last president of Czechoslovakia and the first president of an independent Czech Republic.

Although most of the leaders and signatories of Charter 77 were men, women participated at every level of the movement, and not just as errand runners and menial helpers (although they managed those less glamorous tasks as well). In some ways, the culture of Charter 77 reflected the prevailing attitudes and assumptions about men and women in Czechoslovakia at the time; in other ways, it was very progressive and explicitly egalitarian.

Project of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty profiles three of the women who signed Charter 77 — Jirina Siklova, Bara Stepanova, Petruska Sustrova, and two women who have been influenced by the movement to affect change in their own countries, but it is a tribute to them all — editor in chief of the charter97.org Belarusian news website Natallia Radzina, and Azerbaijani writer and blogger Arzu Geybullayeva.

The leader of the project Emily Thompson writes about belorusian journalist in the following way.

‘A Moral Example’

During the two harsh months she spent in a Belarusian KGB prison after reporting on protests that erupted following the country’s disputed 2010 presidential election, journalist Natallia Radzina had a carefully folded and concealed piece of paper with her at all times. The note, which had eluded the masked men who ransacked her office and dragged her to jail, was a handwritten translation of a letter of support that former Czech President Vaclav Havel, a leader of the Charter 77 movement, had addressed to the demonstrators in Minsk.

Radzina was, and remains, the editor in chief of the Charter 97 website--an independent Belarusian news site that grew out of a pro-democracy declaration of the same name that was inspired by Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia. The Belarusian declaration, which calls for 'devotion to the principles of independence, freedom, and democracy, respect for human rights, solidarity with everyone who stands for the elimination of dictatorial regimes, and the restoration of democracy in Belarus,' was written in 1997 after Belarusian governor Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who is often called Europe’s last dictator, consolidated power and dismissed Parliament in what critics call a coup d’état.

Soon after Radzina joined the declaration after its publication, the declaration was followed by a crackdown on independent media, and there has not been a single election in Belarus since that was deemed free and fair by international observers.

“The Czech Charter 77 was a moral example for us,” said Radzina. “The situation in Belarus was very similar to the situation in Czechoslovakia of those times. Belarus had reverted back to a dictatorship, and we needed the example of Charter 77 to resist the authorities.”

In the run-up to the 2010 presidential elections, Charter 97 was one of the few independent news outlets still functioning in the country. The steady pressure that had been exerted on the media for years intensified. In one of the most disturbing incidents, one of the founders of the web site charter97.org Aleh Byabenin was found dead from an apparent suicide, though his friends, including Radzina, reject this explanation and believe he was killed in retaliation for his work. Pavel Sheremet died in Kyiv in July 2016 in a car explosion that was called a murder by the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office.

“For me it began in March 2010 when the police raided our [Charter 97] offices,” said Radzina. “They beat me and seriously bruised my eye. They confiscated all of our equipment and computers without showing any warrant, and I was taken for interrogations that lasted hours.”

When Lukashenka was declared the winner of the December 19 elections, street demonstrations were violently suppressed and hundreds of people, including opposition politicians, activists, and journalists like Radzina, were arrested and held in KGB cells that Radzina describes as not having changed since Soviet times. For reporting on the demonstrations, she was charged with inciting a riot and faced up to 15 years in prison if convicted.

“Of course, I was shocked by the charges because I knew I was just doing my job and that I hadn’t broken any law,” said Radzina. “But I quickly realized once in prison that [the authorities] were without limits. That they could destroy their opponents in the most brutal way.”

Prisoners at the KGB facility where she was held slept on hard wooden boards and were only allowed to use the bathroom a few times a day--a rule that led Radzina to stop drinking water in order to ease the agony of urgency. She became dehydrated and ill as a result.

“There were only male guards in the prison and it must have been entertaining for them, because we couldn’t close the shower door and they were watching us, which of course was a humiliating experience,” said Radzina. “And anyway they watched us in our cell constantly through a spyhole.”

After two months she was released on house arrest, under condition that she leave the capital while awaiting her trial. She saw what might be her only opportunity, and made a daring escape--first to Russia, then with the help of the UN High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) to the Netherlands, Lithuania, and finally Poland.

In 2011, Radzina was recognized with the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award. In light of her experience, she makes no apologies for the strong activist stance in her work.

“I’m a journalist first,” she said. “But when armed men break into my office, beat me up, and accuse me of monstrous crimes, they make me into an activist.”

Radzina continues to edit the Charter 97 website, to which RFE/RL’s Belarus Service regularly contributes news, from exile in Poland.