Belarusian Amerikanka or Elections Under Dictatorship

26- Andrei Sannikov

- 12.08.2015, 10:06

- 83,052

An honest book by Andrei Sannikov about the 2010 presidential campaign, the Square and the core of the Lukashenka regime.

Written in 2014, the book Belarusian Amerikanka or Elections Under Dictatorship is being prepared for publication. Charter97.org begins to publish extracts from the book with the consent of the author.

Foreword

I was born and grew up in Minsk, in the very center of the city. A month before my birth, in the building where I grew up, the Central Cinema opened, which confirms that the building belongs to the very center of the city. At the very end of the yard there is a Mauritian style building of the former Choral synagogue of Minsk. Now it's the Russian Drama Theater named after Maxim Gorky. Building Number 13 is still standing at the same place where it stood, but from the time of my appearance, it changed its address several times for political reasons. At first it was on Stalin Avenue, then Lenin Avenue, then Francysk Skaryna Avenue, named for the founder of the Belarusian printing press, and now it is on Independent Avenue. Meanwhile, the maternity clinic where I appeared on the earth is still on Volodarsky Street.

Right across from the maternity clinic is the oldest prison in Minsk, the “Volodarka,” nick-named after the name of the street. In the old days, the prison was called the Pishchalov Castle, named for the merchant Rudolf Pishchallo, who commissioned it. The prisoners of the castle were the insurgents of 1831 and 1863, the writers Vincent Dunin-Martsinkevich and Yakub Kolas; the Polish head of state Joseph Pilsudski; and the creator and inspirer of the Cheka-KGB, Felix Dzerzhinsky, the Dracula of Belarus.

Today, School No. 42, the famous “Impermeable Guards,” is also at the same address, on Komsomolskaya Street, just a block from my house. This entire block is occupied by the building of the KGB and Interior Ministry (MVD). The building is notable for the fact that on its façade in the Soviet era were hung enormous portraits of the members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and behind this façade, hidden thoroughly from outside eyes, was the gloomiest Belarusian prison – the “Amerikanka.” For 10 years, I walked to school past the columned entrance to the KGB, and on graduation night, my graduation took place in the Dzerzhinsky Club which is located in this same apartment, right across from the school. We partied until morning and greeted the dawn at the airport.

A few blocks from my house is October Square, which used to be called “Central Square.” In the Soviet era, parades used to be held there along with mass festivities. A block from my house in the other direction is Independence Square, called “Lenin Square” before. The Government Building is on this square, one of the few that remained undamaged by the war, a monument to Constructivism. In the center of this government ensemble is the largest construction in Belarus before the war, a stone Lenin statue on a podium.

I grew up in this district, I know it well, but several years ago I was forced to get to know it anew, to become acquainted with its life hidden from outside eyes.

In 2010, the presidential “election” took place in Belarus, in which I took part as a candidate. The main events related to this “election” in fact took place in the center of Minsk, on the squares and in the prisons of my district. This is what my book is about.

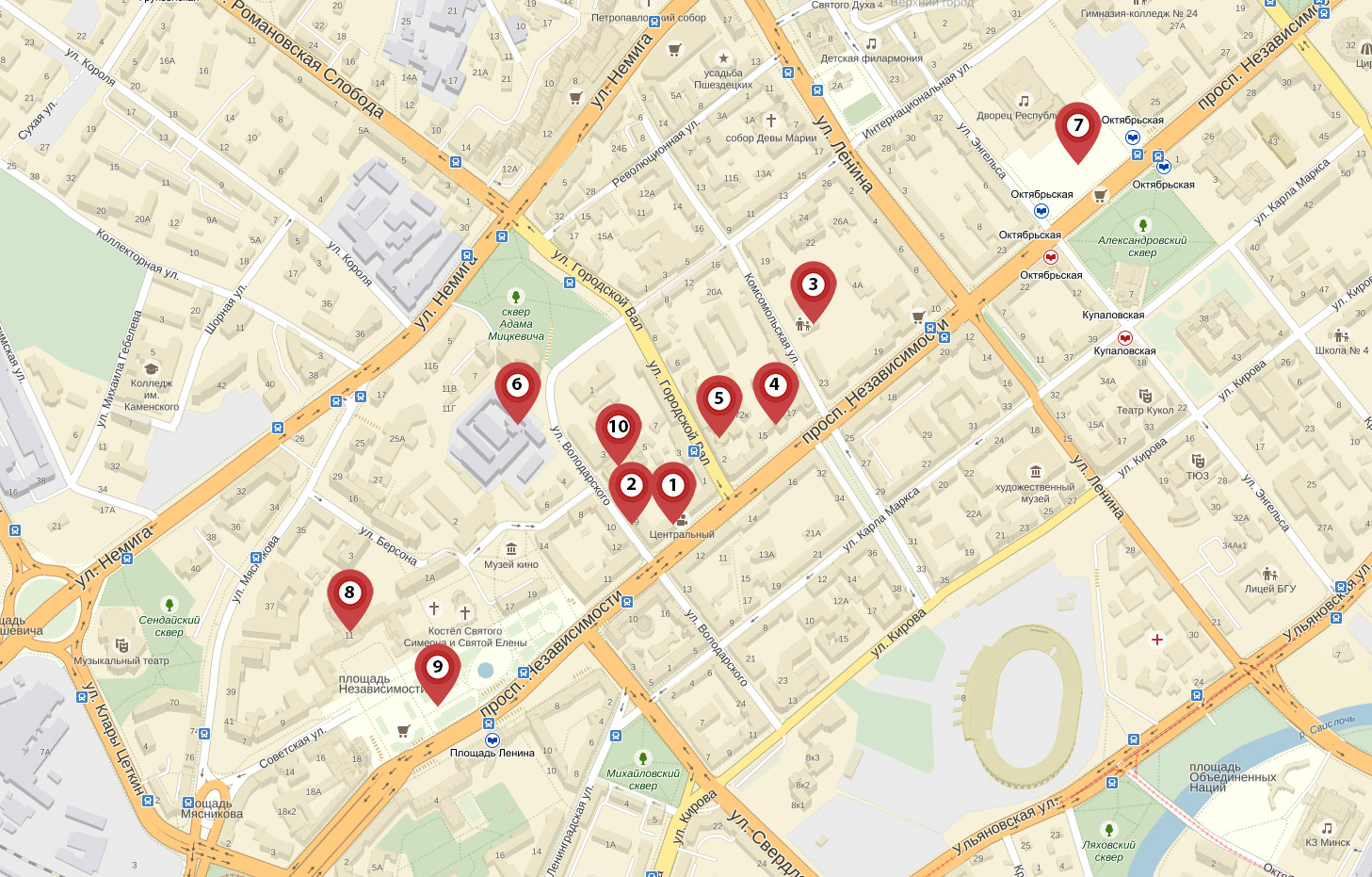

1. Building No. 13, Central cinema2. Maternity hospital No. 13. School No. 424. Building of the Interior Ministry/KGB5. The Amerikanka jail6. The Valadarka jail7. Kastrychnitskaya, or October Square (former Tsentralnaya, or Central Square)8. The Government House9. Independence Square10. The Russian Theatre (a former synagogue)

The Beginning

The public start turned out to be unexpected. I made the decision to run for president of Belarus at the end of 2009, but I did not hurry to announce it. In early March, I was invited to tape a talk show called Forum at the independent Belarusian television channel Belsat. The taping took place in Vilnius, and my wife and I decided to drive there as a whole family. Zmitser Bandarenka joined us. For several months, Irina and I had not been touched when crossing the border, no humiliating searches were made, and no forbidden “information carriers” were sought, and we decided that we could bring Danik with us on the trip.

We were stopped at the border. When such a thing happens, there are several things the border guards can do, instructed by the KGB over the telephone or right on the spot. The mildest thing can be an inspection, a delay of an hour or so, a demand to fill out a declaration, which by law does not need to be submitted if you are not carrying any contraband. This time, the border guards had received the order to take more harsh actions. The customs agents inspected the car, dug through all our things, disappeared somewhere, and did not allow us out of the car. They held us more than three hours. They confiscated the laptop. They didn’t even allow three-year-old Danik to go to the bathroom. That was his first encounter with monsters from the government.

The news that I was planning to run in the elections had already begun to appear in the press and was discussed in opposition circles. So the intelligence agencies had decided to intimidate me in advance. They finally let us go through customs in the evening, but without the laptop. After checking into our hotel, we held a small war council and decided that it was time to announce the decision to run, otherwise, the authorities would think they had intimidated me. Thus it turned out that I announced this during the taping of the show.

A factor that influenced my decision was one rather significant circumstance: Stanislav Shushkevich, the first head of state of independent Belarus, and I had “made up.” I had actually not quarreled with him and could not understand why his attitude toward me had suddenly become so negative. Later, he explained that he had believed the gossip of a certain scumbag. For about 10 years, we had not been in touch and hadn’t even said hello to each other. I was bothered by this. Not only did I respect Stanislav Stanislavovich, I was grateful to him for the clear position he took regarding the removal of nuclear weapons from the territory of Belarus. That had helped me quite a bit in my work at the Foreign Ministry.

Of course, Shushkevich is famous in the world above all for signing in Viskuli the agreement to revoke the Treaty on the Foundation of the USSR, which took place in the Belovezh Forest in Belarus. For that, he got the popular nick-name “Belovezh Bison.”

Now, in the context of the war in Ukraine, you clearly understand that in 1991, he managed to avoid bloodshed, civil war and destruction. The Soviet Union ended peacefully, and that is to a large extent to Shushkevich’s credit, as the host of the historic meeting of the presidents in the Belovezh Forest.

Once he and I went together to meet Lech Walesa in Gdansk, and Shushkevich said to him:

“Lech, you are my hero. What you have done is simply incredible.”

“No, Stas,” said Walesa. “If you hadn’t dismantled the Soviet Union, the tanks would have definitely returned. So the real hero is you.”

In 2009, we finally renewed our relationship, and Stanislav Stanislavovich supported my candidacy.

But before that, there was a very timely initiative by Shushkevich to gather all the political leaders to discuss the situation in Belarus. There were several such meetings in a village, in a hospitable home, according to all the canons of conspiracy. We discussed various formats for taking part in the presidential campaign. In general, at first essentially no new ideas were proposed; there were the same “primaries,” the same “unified candidate” from the opposition. Nevertheless, for me, these meetings were very useful. I looked for the answers to two questions in these meetings: was there a candidate who could be supported during the future campaign, and who could be an ally of our team for the period of this campaign? Alas, the answer to the first question was negative. We had already been burned on this in 2001, and also in 2006 with candidates. The answer to the second question was also not reassuring, since the purposes pursued by different groups were too diverse, and there wasn’t any wish to discuss victory scenarios.

However, the brain-storming that Shushkevich organized, I think, finally convinced Stanislav Stanislavovich to support my candidacy.

Another person had influence on my decision to run. He was a human legend, the elusive “courier from Warsaw” during World War II, “Enemy No. 1” of Communist Poland, the creator and first director of the Polish service of Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe, advisor to four US presidents, Jan Nowak-Jeziorański. I owe my acquaintance with him to Tadeusz Gawin, the first leader of the Union of Poles of Belarus. Tadeusz and I met each other back at the time of the creation of Charter97 civil initiative and to this day we have kept friendly and respectful relations. An honest man and a man of honor, Tadeusz has done a lot both for the Polish minority in Belarus and for Belarusian democracy.

Tadeusz was the one to invite Jan Nowak- Jeziorański to Grodno in 2003 and asked me to come and meet with him. Zmitser Bandarenka and Oleg Bebenin went with me and we immediately fell under the spell of the “grandfather” as we called him among ourselves. He was already 90 years old, and he was forced to take a break to rest every hour and a half of conversation, but even so, he dashingly tossed back a few shot glasses of Berezovaya vodka from Brest, which he liked very much.

After his trip to Grodno, Jan Nowak published an article in Gazeta Wyborcza which was called “Waking up Belarus,” on the need to support Belarusian democratic forces and about how such support corresponds to the state interests of Poland. I then went to Warsaw several times at his invitation, both alone, and with colleagues, and we continued to discuss the situation in Belarus, thinking about how democratic changes could be achieved, and how the West should help. These were not theoretical discussions. Jan Nowak went to Washington in the winter of 2004 and held meetings in official circles and with non-governmental organizations regarding the situation in Belarus. Returning from Washington, he asked me to come to his home in Warsaw and said, “I did my part, persuaded them of the importance of Belarus, now it’s up to you. I trust you and believe in you. I saw leaders in Belarus capable of leading the country, of conducting reforms. You have to go, I will give you all the necessary contacts and recommendations.”

I went in the spring of 2004 and was convinced of Jan Nowak-Jeziorański’s authority, and of his influence. He really was able to stir up the American establishment, to renew interest in Belarus, and his name opened the doors of high offices. American friends of Jan Nowak’s from the days of Solidarity gave me an office for work and meetings. “Grandfather” asked me to report to him if any planned meetings were cancelled. A few times such a situation really did occur, but it was immediately fixed after a call or fax from Jan Nowak. The high-ranking people I met at such meetings usually said, “I couldn’t help but fulfill Jan’s request.”

On that trip, at a meeting with Zbigniew Brzezinski, I gave him an unusual gift. It was his own book, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, in Russian translation and with my inscription. Prof. Brzezinski gave me a puzzled expression when I held out this book to him, and was even alarmed somehow, but after I explained it, I think he was touched. The fact is, Zmitser Bandarenka and Leonid Malakhov and I read this classic geopolitical work aloud and argued and discussed while we sat in the Prison at Okrestina Street in March 2013 after organizing a protest demonstration. We three had signed The Grand Chessboard which I gave Brzezinski.

Jan Nowak’s trip to Washington in the winter at age 90 left its mark on him. He fell ill with pneumonia, from which he could not recover completely. Jan Nowak- Jeziorański died in Warsaw on January 20, 2005. He worked on Belarus right up to his last days.

Once another legendary Pole, Bronislaw Geremek made a historic statement: “Poles have a moral duty before Belarusians. They need our help in order to become free.” Jan Nowak-Jeziorański became for me an example of the understanding of Poles of that debt.

My acquaintance with Jan Nowak, his faith in a democratic Belarus, his sympathies for the people he met with and his words said in Washington that Belarus has European leaders became a serious argument in favor of my decision to run for president of Belarus.

Mikhail Afanasyevich Marinich, probably the most experienced politician in Belarus, also blessed my participation in the elections. He was the mayor of Minsk, a deputy of the parliament, a minister, and the ambassador to Czech Republic and Latvia. He and I got along very well when I worked at the Foreign Ministry, and Mikhail Afanasyevich was minister for foreign economic ties.

In 2001, Marinich nominated himself for president. Ht didn't run but Lukashenka, famous for harboring a grudge, had no intention of forgiving this insubordination. In 2004, Marinich was arrested and accused of theft of equipment from his own organization, Delovaya Belarus [Business Belarus] which was the property of the US Embassy. The US had a system of providing grants in the form of non-compensated leases of equipment like computers. The US Embassy provided documentation refuting this idiotic charge, but this didn’t save Marinich. He was sentenced to five years of labor colony. At the trial, in fact, a Belarusian employee of the American Embassy served as a witness. In Belarus, such a thing is possible.

When Mikhail Afanasyevich was arrested, we began a campaign for recognizing Marinich as a prisoner of conscience and urging his immediate release. We conducted the campaign along with Marinich’s sons, Igor and Pavel, and grew close to them.

Marinich served two of his five years, and suffered a stroke in prison, and barely survived. In fact, he was saved by another political prisoner whose release we were trying to obtain, Aleksandr Vasilyev, or San Sanych as we called him, using his nick-name and patronymic (later he was also to take an active part in my campaign).

Vasilyev noticed that Marinich had not shown up on the grounds of the colony. San Sanych raised a fuss, sent out an alarm to the free world, and only then was the administration forced to provide care for Marinich. He survived through a miracle. After he suffered the stroke, he was just left to die in the barracks, without medication or medical assistance. Apparently that was an order, and in fact coming from the very top, not from the administration of the colony.

He was released from imprisonment in damaged health, but with a determination to fight for change in Belarus. It was easy to discuss things with him and find opportunities for joint actions. His son, Pavel also got involved in my presidential campaign. Pavel was energetic, communicative and even at times a risk-taker – which was necessary for the campaign. Pavel also had to hide from the police after December 19, 2010, and then fled from Belarus to Lithuania. Once he was safe, Pavel couldn’t help but call the telephone which had been carefully left with his mother by the KGB agents. Once he was convinced that on the other end of the line there was a KGB officer, Pavel let loose with everything he thought about him, his masters, Lukashenka, and so on – in uncensored language. In Vilnius, Pavel Marinich helped to restore the work of the Charter97 web site.

The support of such political “heavy-weights” as Stanislav Shushkevich and Mikhail Marinich played an important role in the further formation of the team. We had the best backbone, I think, in Belarus. With such a team, you could win in any country of the world where there are elections.

Oleg

A key figure was the founder of the site charter97.org, Oleg Bebenin. His tragic death in September 2010, at the very start of the campaign, without a doubt was an extremely brutal attempt by the authorities to stop our participation in the elections. It was very hard for me to make the decision to continue the campaign. All the abstract conversations with friends about how each one chooses for himself the degree of risk ran up against the real death of a close friend, a young man. After all, it could continue. On the other hand, to stop our fight in our situation could be even more dangerous – the mean-spirited government would strive to the end to retaliate against us. We discussed what to do and decided to continue the campaign, among other reasons, in memory of Oleg. Those who didn’t want to take the risk left. There were not many of them.

Oleg was a jack of all trades, he could do anything, and did do everything, and in fact equally effectively. A journalist and the founder of the Charter97.org site, he became the specialist who was needed at that moment. He took care of the transportation and the loud-speaker equipment, the print production and the moves from office to office. He could not have left life willingly. Oleg very much loved his youngest son Stepan. He and I grew even closer on those grounds. Oleg was younger than me by about 20 years, and Stepan was a year older than my son, Danik. And I think Oleg found enjoyment in speaking with me about sons, and pulling rank a little bit over me, as the more experienced father. We spoke of our children almost every day, starting in the morning.

To this day, I use accounts in social networks which he opened. To be honest, I can’t accept the thought to this day that he’s gone, even though I saw his cold body on the evening of September 3, 2010, and saw him off on his final journey.

Oleg’s brother, Sasha, was the one to report to me that Oleg had been discovered hanging at his dacha. On the morning of September 3, Katya, Oleg’s wife, called the office, and told us that he had not spent the night at home, and she was worried that something had happened to him. Oleg wasn’t at work, either. I was at home, and Oleg and I had agreed to meet that afternoon. We began calling all the possible telephone numbers we could. The previous evening, Oleg had planned to go the premier of an American film with his friends. He was a film lover and never missed a single premier. Later, his telephone calls and SMS messages would be recovered, showing that he had confirmed to friends that he would be at the movie theater.

Katya called once again and reported that she had not found the keys to their dacha. She asked her friends to drive up out there and see if Oleg was there. Sasha, Oleg’s brother, also made the trip. He then phoned that morning and reported the terrible news. Zmitser Bandarenka, Aleksandr Otroshchenkov, Fyodor Pavlyuchenko and I went out to the dacha, to Oleg.

We arrived and began to wait for the police. It was very cold. We waited for several hours. The first questions were already beginning to appear. The precinct was not that far away. Why wouldn’t the police come right away after getting a report that a man’s body had been found? One explanation: they were coordinating their actions with higher-ups.

Together with the police, we took part in looking over the scene of the tragedy. There were a lot of strange things. A kind of unnatural cleanliness in all the rooms was surprising. There were only a few ashes in the fire place, perhaps from one log, or some papers. Clearly not sufficient in order to heat this spacious house. There were no traces of any recent presence in the home of a person except for the body of Oleg, hanging in the door way. He wasn’t even hanging, but nearly kneeling. His ankle was unnaturally turned out, as if it were broken. In the room, there were, demonstratively placed against the wall, two empty bottles of Belorussky Balzam, rot-gut that even bums wouldn’t drink.

The two cops who came were noticeably tense. When we drew their attention to some details we thought were important, they inevitably tried to convince us of the opposite. On the bones of the fingers of Oleg’s left hand were bruises which might be evidence of resistance. Oleg looked as if death had come suddenly. There was no rigor mortis or other signs that a lot of time had passed, yet after the autopsy, we were told that it had all happened on September 2, that is, a day before the discovery of the body.

There were many details that didn’t fit into the hypothesis of suicide. Nevertheless, only that hypothesis was looked at by the official agencies. Oleg’s friends began to be called in for questioning. And then it was discovered that the investigation was trying to push another version of his death, that Oleg had supposedly killed himself over some dark financial matters.

Information began to be “leaked” to the Internet about how he had supposedly obtained a large sum of money. Then information was even dropped to the effect that I had settled scores with him. One of the investigators kept stubbornly asking me over and over again about the last meeting with Oleg, a day before his disappearance. He showed me papers with typed-up notes about my whereabouts. I thus learned that it was very easy to determine the coordinates of a person through his mobile phone. With a cell phone, this can be determined with accuracy to a few meters. The investigator was particularly interested in the question of why we were in a building, and then went outside. I was forced to explain that we went outside so as to avoid the bugging by his colleagues in the intelligence agencies, and for this, we took the batteries out of our telephones.

Realizing that Oleg’s death continued to be used to place pressure on us, we began to demand an independent international investigation. Journalists also made this demand. Unexpectedly, even Lukashenka began to say that Oleg’s death wasn’t a suicide.

The state media wrote about this:

Until today, the Belarusian prosecutor’s office said that this was a suicide, but on November 4, in an interview with a Polish journalist, Aleksandr Lukashenka stated that he was certain that the case of the Belarusian journalist Oleg Bebenin was criminal in nature.

“I believe, that the fact that this is a criminal act will come out, and someone will look very bad, those who today are casting a shadow on the government. As they say, the cap burns on the thief’s head. I am guilty of the fact that this happened in my country,” BelaPAN quoted Lukashenka as saying.

According to Lukashenka, any event in Belarus is connected to politics.

“As with that Bebenin. Listen, I didn’t know at all who this opposition journalist was,” said Lukashenka. “It turns out that he wrote something on the Internet on Charter. God bless you. So much is written on this Internet, so many bad things about the government…”

Lukashenka also addressed the topic of the disappearance of prominent people in Belarus.

“As for the disappeared people in our country, I’m the one most interested in this. For example, Dmitry Zavadsky worked as my cameraman, he was a good guy. What kind of politician was he, what kind of rival? And that I, as I was accused – that Lukashenka either knows about it or gave the order. And what was that guy guilty of ? Or Gena Karpenko, who died in the hospital, what has Lukashenka got to do with it? If you want to investigate this – please, come and investigate.”

It became clear that they would try to fabricate a case against us, since our presidential campaign was already visible all over the country. The authorities decided to invite OSCE experts to Belarus, supposedly responding to public demand. That made us cautious, both the fact that the dictator had doubts about the suicide story and the sudden, quick decision regarding the international expertise. Particularly memorable was the involvement under the OSCE of a German “expert,” Dr. Martin Finke, to make an appraisal of the “terrorism case” against Nikolai Avtukhovich, a businessman, who had defended his rights and uncovered facts of corruption, for which he was thrown in prison. Dr. Finke dug into some papers, and without any doubts concluded that the case was justified, but then the case fell apart..

I tried to involve as an expert the Finnish specialist Helena Ranta, my good acquaintance, a brave woman and also a human rights advocate. Helena Ranta was famous for heading a group of forensic experts working in the former Yugoslavia and confirming the facts of genocide. I wrote and phoned her, and at last I got through, but the connection was terrible, and I understand only that she was in Nepal and would not be returning soon. Later I learned that in Nepal, she had searched for the burial sites of five students who had been arrested and then went missing in 2003. She managed to find all five graves, but she was not able to help us.

I suspect that just as in the case of Avtukhovich, Oleg’s case would not have gone by without the mediation of some diplomats, and agreements with the authorities that the “experts” would guarantee the appropriate results.

That’s exactly what happened. Recalling the scandal with the German expert, two Scandinavian specialists came incognito and didn’t reveal their names. They studied the papers offered them, spoke with relatives and friends and confirmed the suicide variant. I was unable to meet with them, although we had a meeting scheduled. For some incomprehensible and strange reasons, on that day, my flight from Prague, on which I was supposed to return to Minsk, was delayed. There were clear September skies and no technical reasons were reported, but I arrived after the experts themselves had already flown out.

Zmitser Bandarenka met with these specialists and assessed their “activity”:

“On the basis of the information with which I acquainted myself from the conclusion of the OSCE experts, I can say two things. The experts confirmed that they did not conduct their own investigation, and could not conduct it, but only familiarized themselves with papers which were provided them by Lukashenka’s prosecutors and police. And the only claim that they managed to make was this: that Oleg Bebenin’s death came from suffocation. We, friends and colleagues of Oleg, had said from the outset that Oleg did not hang himself, he was hanged, and that the authorities announced to the mass media even before the autopsy was completed that Oleg Bebenin had ended his own life. Other variants of the Belarusian police and prosecutor’s office were not reviewed or investigated from the outset.

The impression was created that the experts who came were a plaything in the political games of the Belarusian regime and those Western politicians who try to save the last dictatorship in Europe. On the basis of the facts which the experts confirmed who came for three days, it is completely impossible to speak definitively about a suicide. The phrase “OSCE expert” would soon become a household word in Belarus, since the people who came to the country did not take into account the fact that Belarus is a totalitarian state and that it was impossible to make their conclusion only on the basis of papers provided by the regime’s enforcement agencies.

The previous OSCE expert who had come to Belarus from Germany and made the conclusion on the case of the political prisoner Nikolai Avtukhovich also fell into a trap when, on the basis of documents of the investigation, he confirmed the prosecution’s claim that the businessman was a terrorist. But everyone knows that Avtukhovich’s case fell apart even in Lukashenka’s court. After the government changes in Belarus, a real investigation into the death of journalist Oleg Bebenin will be made, along with other sensational cases in Belarus.

At the Amerikanka, as the KGB’s prison is called, where we landed after the elections, the story of the investigation of Oleg’s death had an unexpected continuation. The KGB officers confirmed to Zmitser Bandarenka, Natallia Radzina, my wife and me, that Oleg was murdered. Col. Orlov, head of the KGB pre-trial detention prison also told us this, as well as Igor Shunevich, the head of the investigative department, and then later the “counter-revolutionary” division of the KGB, who was for his “services” in 2012, made Interior Minister. To be sure, they tried to suggest to us that Oleg’s murder was at the hand of some “strangers,” and that the KGB supposedly had nothing to do with it.

But Oleg was gone. In the heat of the presidential campaign, we thought more of how to fill the breaches, the serious holes which had to be patched after his death. Today, we keep remembering more and more what he was like. You realize that you still miss him. You remember that Oleg was ready to sacrifice a lot for the sake of the common cause. Sometimes, even things that were valuable by any measure.

Once, in order to create a temporary alliance before some action which we were preparing, Oleg sacrificed to a certain intractable politician an entire album of rather valuable stamps which he had once loved to collect. The politician appreciated the generosity of the gift and joined the coalition. This is a point not about the mercantile nature of the politician, but about Oleg’s nobility.

He had a remarkable trait: to take an interest in what was important and interesting for his friends. And after a time, these interests would become his own. I was sincerely happy when films and music which had influenced me became part of his system of values entirely naturally and sincerely, although we were in different generations.

Oleg is gone. No doubt he would have sat with us in the Amerikanka as well, and at the colony, and would have once again been an indispensable bundle of energy and source of optimism…

THE FEMALE «STALIN»

- He spoke with a soft voice. That was the matter of Party functionaries in the Soviet era. That was how they raised their significance, forcing their interlocutor to unwittingly strain their ears and try to make out the incomprehensible mumbling of some puffed-up turkey. Zaitsev spoke softly, into his mustache. He primarily looked at the table, occasionally threw a glance to me which evidently was supposed to seem penetrating. He smoked. To be sure, here, he messed up. “Stalin” couldn’t smoke slender women’s cigarettes.

I wouldn’t have known that I was being taken to the chairman of the KGB, if on the night before, they hadn’t kindly thrown a newspaper with photographs of all of Lukashenka’s government into my cell. Before that, it had never occurred to me to take an interest in how this or that “minister” looked. I looked at the newspaper and therefore recognized Zaitsev. Otherwise, I would have thought that he was the usual KGB man of a rank lower.

The bringing of me to Zaitsev was also staged in the Stalinist traditions. I was taken out from my cell on December 31, not long before lights out. The cell was getting ready to celebrate New Year’s; we had even made selyodka pod shuboy (literally “herring in a fur coat,” a regional dish made of herring covered with layers of vegetables and mayonnaise), thanks to the herring, beats and onions that they served us from time to time for dinner. On the window sill stood a Christmas tree made from an upturned stem of grapes with ornaments made from the foil of cigarette packets. Right before Zaitsev, I had been taken to Orlov, and I had not even asked him, but rather confronted him with the fact that we planned to celebrate New Year’s. Orlov said something about the regimen, but not very convincingly. I realized that they would not forbid the prisoners to stay up after lights out that night.

After the appearance of a large group of people detained December 19 at the Amerikanka, sometime within a few days, the prison officials turned off the outside antenna. There were television sets in a lot of the cells, the reception was bad, but even so, at least something could be seen. It was at least some distraction from the grim reality. They turned the antenna off, but by KGB habit, they lied that something had broken, and the population of the Amerikanka was left not only without entertainment, with one-sided news, but without a clock, because this was not allowed in the cells.

I earned the sincere respect of my cell-mates by suggesting a way to get the television working. We made an antenna out of a pair of eyeglasses with a steel frame. A cell-mate had an extra pair. We took the plastic ends off the sides, stuck it into the mount, and the signal began to get through. Then we perfected our “antenna,” adding on to its end a metal prison mug, a “helmet.” By turning this “helmet,” we could get rather tolerable reception. Our “antenna” received more channels than a stationary antenna.

The table was set, the television was working, we were taken to the shower, we had only to wait until midnight and greet the incoming year 2011. And suddenly I was jerked from the cell, not told a thing, and taken to God knows where.

I had not given any testimonies, so it was not to the investigator. They took me out of the prison building and into the KGB building. So that meant I was going to see the investigator anyway. I walked with difficulty, my leg was still hurting after the beatings. They took me along the long corridor and brought me to an office in the annex. There was no one in the office. It was a typical but for one person, which meant it was for a boss. Memory has blanked out the setting of the room, but I recall that I looked around it. I was offered to sit down. I sat down with difficulty in a chair against the wall; the guard who had brought me stood next to me. The boss came in, it was KGB chairman Zaitsev, a man with a mustache, and asked me to move to the table, and let the guard go.

Zaitsev offered me coffee. I didn’t refuse. I hoped that the bosses’ coffee would be good quality. It turned out to be shitty, in keeping with the institution.

Zaitsev began to speak, and I couldn’t believe my ears. Out poured such a lot of Soviet nonsense, familiar to me from bad propaganda films, that I found it difficult to believe in the reality of what was happening. The Party Stalin-style manner of speaking just barely audibly in this case was relevant. I didn’t have to strain to hear, there was nothing important for me or for further communication with the henchmen in Zaitsev’s torrent of words.

Espionage…foreign agents…coup d’etat…terrorism…millions of dollars…Gusinsky…Berezovsky…explosive devices… fighters… weapons…the rest of them cracked…you may not get out of prison…a pure-hearted confession…think of your family…we know everything…millions of dollars…treason…who is running this…

Sometimes Zaitsev was simply touched and disheartened.

“You know what all the spies and agents seek in our country? What their purpose is?”

“Perhaps, security?” I suggested, mistakenly thinking that I was dealing with someone responsible for this very security.

“Their purpose is our people. That is our main wealth and our secret.”

“???”

Dumping all his delirium on me, Zaitsev at a certain point became beside himself and forgot that he should speak in a quiet and persuasive voice. When I, objecting to him, said “This is my city and my country,” Zaitsev switched to a shout. “You’re presuming a lot, who are you, and who gave you the right!” he shouted. That was understandable, he was not from Minsk like most of my henchmen.

The forced conversation finally ended. I was brought to a cell where two brood hens, let’s call them “animal” and “cop,” continued to work me over. They cited as an example the fact that at least three of their former cell-mates from among those arrested on the Ploshcha who were “smarter,” and wrote to Lukashenka, who correctly talked with Zaitsev and for a long time, were now either getting out or about to get out any minute. I began to realize why I had ended up in this cell. They had the best indicators for re-education.

Nevertheless, we celebrated New Year’s with the tree, herring “in a fur coat” and Russian and Belarusian pop music on the television set. Everything as it should be.

The next coerced conversation with Zaitsev took place on January 16. They prepared me well for it. Every day, they chased me, with my sore leg, up and down the steep stair case with all my things, including the mattress and the bedding, to a personal inspection in a cement basement. They stripped me naked, and forced me to stand naked against the wall in terrible cold, gleefully throwing my things on the floor, and forcing me to squat down on my sore leg. They pretended to move me to another cell, for which I had to drag a wooden pallet, aside from the bedding, upon which I slept on the floor. People in masks stealthily beat me on my feet, cracked over my ear with an electric taser, and banged on the iron staircase with clubs as I climbed down. When they took me out of the cell, they tightened the hand cuffs painfully on my wrists, they made a “sparrow,” lifting up hand cuffs tied behind my back to the point of crunching in the joints, and painfully jabbed me in the back with clubs.

The “animal” then got to work on me when I got back to the cell, very cunningly winding himself up to a hysterical pitch, that because of me, people were suffering. Later, the “cop” started in nicely trying to persuade me to give testimony.

The second time, on January 16, 2010, Zaitsev seemed even more disgusting. He demanded acknowledgements. He was noticeably nervous, and even broke into angry tirades directed at me, forgetting about his “Stalinist” mask. Apparently, he needed to have results showing the “exposure of the conspiracy,” and he didn’t have any.

Zaitsev threatened my wife and son. I could not help but take extremely seriously his exclamation that the most brutal things would happen to them. What could be harder when Irina was next door in a cell of the Amerikanka, and they tried to put Danik in an orphanage. It became clear that Zaitsev was threatening physical reprisals over them. To my shocked question, “how can you?” he whispered something like “enough standing on ceremony.” It is hard to imagine that a minister, and even one bearing a general’s rank, would openly threaten the murder of a woman and child.

With difficulty, I withstood the second meeting with the chairman of the KGB, and thought that I would lose my nerve at the next meeting. But fortunately, there wasn’t a third meeting.

Despite the general threatening tone of the conversation. Zaitsev twice “broke down.” The first time was when he asked what the slogan of my campaign meant, “Time to change the bald tire!” Saying it, he couldn’t help but break out laughing and then immediately began coughing in fright. He knew well that even the main KGB chief was monitored and likely we were being recorded on a camera.

The second “break-down” was significant: he told me that only two of the candidates for president had gathered the necessary number of signatures. Later I tried to summon him to court as a witness so that he confirmed this. Of course he didn’t come, and of course he wouldn’t have confirmed it even if he had come. For then it would turn out that, confident in his impunity and in the durability of the regime, Zaitsev had openly admitted to me that the authorities falsified the elections. Out of 10 candidates for president, only two gathered the necessary 100,000 signatures. That meant that two should have been registered. I think Zaitsev was putting Lukashenka “in parentheses” and meant the two opposition candidates. But he wouldn’t have made an offense against the truth if he had spoken about all 10 candidates. Lukashenka wouldn’t have gathered all the signatures honestly. It is hard to imagine a more absurd situation: the chairman of the KGB admits the elections were falsified… in a conversation with a candidate for president, accused of organization of a protest against the falsification of the elections.

Zaitsev’s admission was openly impudent. He was essentially admitting that the authorities realized that the dictator was losing and cynically manipulated the electoral processes, brutally suppressing a peaceful demonstration, protesting against these manipulations, and throwing people in prison for the fact that they would not accept the falsification.

CONTINUATION, CHAPTER "THE DIFFIDENT TURNKEY"

CONTINUATION, CHAPTER "METRO BOMB"

CONTINUATION, CHAPTER "I REMAIN A PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE"

CONTINUATION, CHAPTER "DON'T SMARTEN DICTATORS"

CONTINUATION, CHAPTER "ONLY THE HANDOVER OF POWER IN BELARUS CAN LEAD THE COUNTRY OUT OF THE CRISIS"